The CND symbol is one of the most widely known symbols in the world; in Britain it is recognised as standing for nuclear disarmament – and in particular as the logo of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). In the rest of the world it is known more broadly as the peace symbol.

What does it mean?

It was designed in 1958 by Gerard Holtom, a professional designer and artist and a graduate of the Royal College of Arts. He was a conscientious objector who had worked on a farm in Norfolk during the Second World War, and explained that the symbol incorporated the semaphore letters N(uclear) and D(isarmament).

He later wrote to Hugh Brock, editor of Peace News, explaining the genesis of his idea in greater, more personal depth: ‘I was in despair. Deep despair. I drew myself: the representative of an individual in despair, with hands palm outstretched outwards and downwards in the manner of Goya’s peasant before the firing squad. I formalised the drawing into a line and put a circle around it’.

Eric Austen, who made the first CND badges, added his own interpretation of the design: ‘the gesture of despair has long been associated with the death of Man and the circle with the unborn child’.

Gerard Holtom had originally considered using the Christian cross symbol within a circle as the motif for the first major anti-nuclear march from London to Aldermaston, but various priests he had approached with the suggestion were not happy at the idea of using the cross on a protest march.

Later, Christian CND would use the symbol with the central stroke extended upwards to form the upright of a cross. This adaption of the design was only one of many subsequently invented by various groups within CND and for specific occasions – with a cross below as a women’s symbol, with a daffodil or a thistle incorporated by CND Cymru and Scottish CND, with little legs for a sponsored walk etc. Whether Gerard Holtom would have approved of some of the more light hearted versions is open to doubt.

First public appearance

Gerald Holtom had been invited to design artwork for use on what became the first Aldermaston March, organised by the Direct Action Committee against Nuclear War (DAC). He showed his preliminary sketches to a DAC meeting in February 1958 at the Peace News offices in North London.

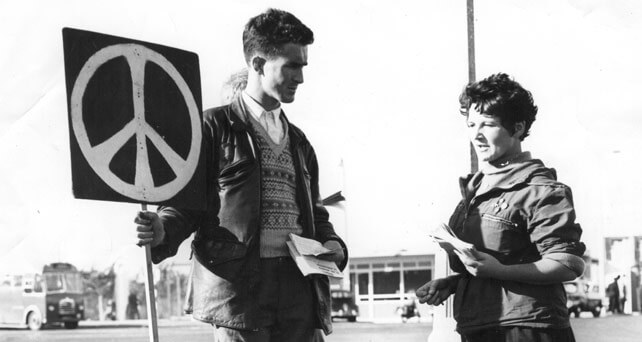

The Direct Action Committee had already the previous year begun planning that first major anti-nuclear march from London to Aldermaston, where British nuclear weapons were and still are manufactured. On Good Friday in Trafalgar Square, where the weekend march began, the CND symbol first appeared in public. Five hundred cardboard lollipops on sticks were produced. Half were black on white and half white on green. Just as the church’s liturgical colours change over Easter, so the colours were to change, ‘from Winter to Spring, from Death to Life’. Black and white would be displayed on Good Friday and Saturday, green and white on Easter Sunday and Monday.

The first badges were made by Eric Austen of Kensington CND using white clay with the symbol painted black. Again there was a conscious symbolism. They were distributed with a note explaining that in the event of a nuclear war, these fired pottery badges would be among the few human artefacts to survive the nuclear inferno.

Misrepresentation and misuse

There have been claims that the symbol has older, occult or anti-Christian associations. In South Africa, under the apartheid regime, there was an official attempt to ban it. Various far-right and fundamentalist American groups have also spread the idea of satanic associations or condemned it as a Communist sign. However the origins and the ideas behind the symbol have been clearly described, both in letters and in interviews, by Gerald Holtom. His original, first sketches are now on display as part of the Commonweal Collection in Bradford.

Although specifically designed for the anti-nuclear movement it has quite deliberately never been copyrighted. No one has to pay or to seek permission before they use it. A symbol of freedom, it is free for all. This of course sometimes leads to its use, or misuse, in circumstances that CND and the peace movement find distasteful. It is also often exploited for commercial, advertising or generally fashion purposes. We can’t stop this happening and have no intention of copyrighting it. But we do ask commercial users if they would like to make a donation towards CND’s work and very often get a positive response.

Symbol of peace

The symbol continues to be used as shorthand for peace and hope. Recently, it’s been seen at refugee camps and climate change protests, as well as at our anti-Trident demonstrations. CND will continue to be proud of this iconic symbol created by Gerald Holtom and we’ll continue to use it to inspire our anti-nuclear campaigning until we get rid of Trident.